The most recent step in the evolution of portfolio construction practices has been a shift from an asset allocation–centered process to a more comprehensive risk allocation–based process. Cambridge Associates’ Risk Allocation Framework considers multiple dimensions of risk and return trade-offs when building portfolios and evaluates the consequences of risk allocation decisions during normal and stressed markets.

Yet the problem became that several of these more recently introduced “asset classes” actually have common risk factors that cross “asset class” boundaries. Examples include equity risk in distressed securities and natural resources equities, and illiquidity risk in hedge funds and commingled funds particularly in stressed environments. Thus it became increasingly difficult to recognize, without significant analysis, just how much equity risk (for example) might be embedded in a portfolio that owned lots of assets not named “equities.”

To clarify matters, investors increasingly have constructed portfolios on the basis of the role they expected different kinds of investments to play in the portfolio (i.e., role-in-portfolio exposures), even if they still allocated investments to traditional asset classes.

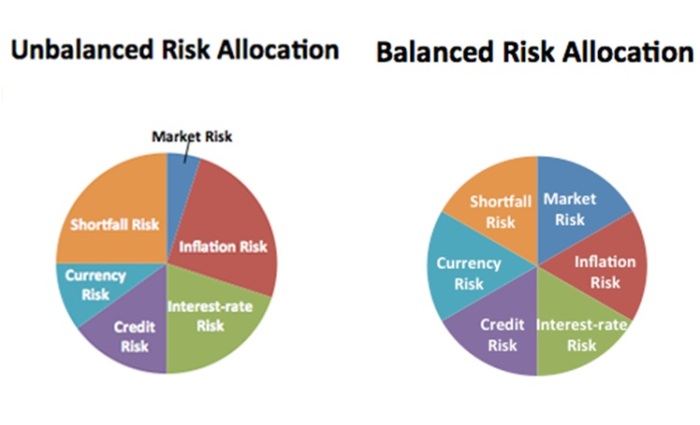

The Risk Allocation Framework takes this evolution a step further by considering not only the role that different investments might play in the portfolio, but how and in what ways such investments contribute to or mitigate various forms of portfolio risk. The framework combines careful attention to risk allocation in the context of the risk sensitivities and limitations of a long-term investment portfolio (LTIP) given its role in the broader organization. Since risk exposures move over time, we monitor risk allocation and performance attribution dynamically.